Article 2: Size Matters

Your fund size is your strategy. Why sizing the fund properly is more important than somebody realize.

Intro

There’s an old saying in the Venture Capital industry:

“your fund size is your strategy”

We cannot agree more. The investment approach should drive the fund size and not vice versa. It’s the first variable a GP should consider, and it’s one of the first elements LPs will investigate, whether you are raising your first, second or tenth fund.

It's a complex topic with significant implications across multiple areas, including investment strategy (stage of investment, ownership target, lead/follow, # of investments), competitive positioning, geographic ecosystems (US, Europe, Israel, ASIA), exit scenario, number of general partners, personal incentives, etc.

The emergence of mega-funds in recent years has sparked even more debate with several GPs becoming very vocal about the consequences on the ecosystem. Last Pitchbook data provides a staggering picture of it. Over 50% of the 2024 LP allocation went to 9 firms only (including a16z, General Catalyst, Thrive Capital, Flagship Pioneering, TCV, ARCH Venture Partners, Norwest Venture Partners, Tiger Global).

In other words, you can’t talk about a venture capital strategy without first addressing fund size - it’s fundamental for delivering consistent performance to your LPs, establishing your position in the industry and building a strong brand. This doesn’t mean raising the same amount for each fund, but rather focusing on raising exactly what’s needed to execute your strategy and succeed in the game.

In this piece, we’ll go through the topics touching upon:

The basic logic of fund sizing;

The implied conflict of interest of fund size;

Some historical data analysed by us;

Big Funds on the Rise: So What?

Logic Behind Fund Sizing

The fund size for a venture firm is like the fuel for the engine. The right one will not only allow the engine to work but also guarantee higher performance. Pick up the wrong one, and you’ll end up breaking everything.

In our view, several key interconnected variables should be taken into account in the decision-making:

The themes the fund invests against - some sectors require more capital than others to pursue the same strategy (e.g., DeepTech, Biotech, Quantum, Infra AI);

The stage the fund is focused on - each stage is characterized by different sizes - as a seed or early-stage investor, you “typically” don’t seek as much capital as growth investors.

The role in a deal (lead vs follow) - if the fund leads most investments, it'll need more capital for each one than if it follows with smaller checks;

The competitive environment - who else is competing based on the strategy defined? Venture capital is evolving and growing, leading to more capital being available for funds that are eager to deploy larger amounts of money to win deals. Even if the GPs are disciplined about valuations, you can’t avoid the game on the field. Just because 10 years ago you could win deals with less capital doesn’t mean you can do the same today (and we’re not talking about FOMO-driven deals).

Geographic Ecosystem - how mature is the target market? The average deal size tends to vary by geography - investors in North America usually need more capital to secure the same percentage of ownership that they could in Europe with less money**.** So if you're a European fund investing solely in Europe and aiming for high returns for your LPs, you wouldn't need as much capital as a US fund pursuing the same strategy in North America. The exit landscape also plays a role - in Europe, there are fewer exits and they tend to be smaller compared to the US, making it harder to generate strong returns and get money back to investors quickly.

#GPs - having more partners can justify a bigger fund size. While it's not mandatory to raise more money just because you have more partners, it makes sense since you have more resources in terms of time and expertise. For a solo GP, raising a €200M fund is harder to justify (though there are some rare exceptions).

Portfolio Management Strategy (Platform) - By their third or fourth fund, some VC firms build an in-house platform and bring on a dedicated team to run it. This means raising more capital to cover the additional overhead, but the goal is to provide better support to portfolio companies and generate stronger returns. Does investing in a platform pay off? We'll analyze this in the following articles.

To give you a practical example of it:

Investment strategy: seed stage and sector agnostic, lead, hands-on support (platform or dedicated team).

It implies that the firm should at least invest € 1-3 Mn per entry ticket, at least 4-6 companies per year

Ecosystem: Italy, which is characterised by a low entrepreneurial rate, relatively low valuation, long exit timeline, and low exit value.

We should expect a portfolio strategy that favours more diversification at the earlier stage and some reserve to double down on the few winners. Thus 6 portfolio companies and a substantial reserve strategy

The competitive Environment: no big competition inflating valuation or cannibalizing the market

It implies that with € 1 Mn of average entry the fund may get the desired allocation.

Therefore, with 6 portcos/year * € 1 Mn/portoc4 years= €24 Mn. Adding 40% reserve → € 40 Mn deployment capital. With management fees equalling 20% of fund size → 40/0.80% = €50 Mn*

The Implied Conflict of Interest of Fund Size

The venture capital business model is the so-called 2-20 (standard for the industry, it could be even higher for top-tier funds, 2.5/25). Meaning:

2%-2.5% of management fees over the assets managed “paid” yearly by LPs to GPs

20%-25% of carried interest, i.e., 20%-25% of the excess profit generated by the fund managers.

Such models were first introduced in Venice during the Middle Ages to align the interests of sailors and financiers involved in commercial expeditions to the Middle East. Arthur Rock later adapted this concept for the venture ecosystem, as it ensured that GPs had a strong incentive to maximize the enterprise value of portfolio companies while avoiding the need to go without a salary for 10 years, which could otherwise lead to a short-term focus.

However, over the years some weird dynamics emerged:

Returning capital to LPs has become increasingly challenging due to the power law distribution and recent trends, such as companies staying private longer and tougher exit conditions. Contributing factors include stricter regulations and higher IPO standards, among others.

LP capital becomes more accessible, especially when it is “free” (2020-21) and other asset classes fail to perform as expected.

Thus, some managers may be incentivized to increase assets under management (AUM) at all costs to secure substantial fees, playing it safe with limited motivation to maximize upside potential. As an LP, it’s crucial to address this, especially when investing in emerging managers. Be sure to ask about their plans for future fund size and the evolution of their GP partnership. As a GP, you should ask yourself what you want to build over the next 10-20 years - will you care more about fees or results (carry)?

We think the topic of fund size is getting more nuanced when considering competitive dynamics and the evolution of the ecosystem, but it’s something that we’ll touch on in the last paragraph.

Performance by Fund Size

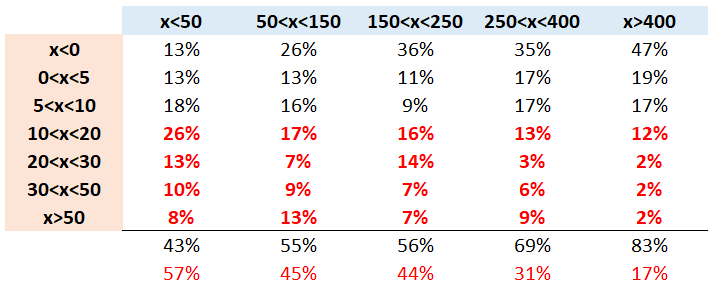

We analysed Preqin data for over 2k funds across the world (from 1969 vintage). We sorted out only the realised funds (800) and divided them into five buckets:

Micro VCs (x<50 Mn): Typically, emerging managers (1st/2nd-time funds) who want to prove themselves before scaling up. Sometimes, these are also small managers who prefer to stay small due to their strategy.

Small VCs (50<x<150 Mn): Usually seed investors, carry-oriented with an agnostic approach. Once they gain some traction with previous funds, they scale up a bit to pursue the same strategy while gaining more ownership.

Mid VCs (150<x<250 Mn): US funds' sweet spot. “Large” seed (2-4 GPs) or early-stage funds with a “traditional” approach to the market. This is where most of the top-tier funds choose to focus instead of continuing to scale.

Mid-Big VCs (250<x<400 Mn): here, we have a mix of VC funds, ranging from top early-stage investors to large seed funds, as well as deep tech investors who need more capital to execute their strategy, all the way down to smaller growth and late-stage funds. That’s probably why, as we’ll see, the performance isn’t exciting – there’s too much “noise”.

Big-Multi Asset VCs (x>400 Mn): the last bucket is characterised by large funds, typically growth/late-stage ones, but it also includes 'insane' seed investors (expensive structure) and large early-stage funds. Also, it includes multi-asset investors who raise significant amounts of capital to invest across the entire spectrum, from seed to pre-IPO, covering all stages to reduce the asset class risk. These are the ones, as mentioned above, that are currently attracting the most LP attention, even if the performance is what it is (as we’ll discuss later).

We performed two different analyses. The first examines the performance dispersion (%) based on the number of funds, while the second is a linear regression. For the metrics, we used DPI, as we focused only on realized funds, and IRR, due to its importance in comparing investments.

Dispersion Analysis

DPI

IRR

Key findings of our analysis:

Micro wins: not surprisingly, small funds outperform others, with almost half (46%) generating more than 2x net money-on-money and 22% generating more than 3x. Additionally, 57% have a Net IRR above 10%, while 31% exceed 20%. These are extraordinary figures for the asset class - the dream for every LP. Moreover, 41% of these funds have delivered between 1x and 2x net to their LPs, while only 13% have returned less than 1x, which is impressive compared to other buckets.

Surprise on Small: while performance isn’t bad overall - 3% of funds achieve >10x returns (compared to “just” 1% in Micro funds) and 13% more than 50% IRR (8% Micro) - there’s a risk of getting stuck in the middle (e.g. leading when you don’t have competitive power/powder in the market or geo that are complex). This group might be described as a “transition” bucket, especially in the US, where second and third funds often aim for larger sizes but frequently fall short. Additionally, many non-emerging funds fall into this category by struggling to reach their target size and closing smaller funds than planned, often due to a lack of a strong track record. The key difference from Micro Funds is that the 14% of returns missing from the top tier (x > 2) tend to fall into the lower range (0 < x < 1).

Mid VCs above the average: We didn’t expect better performance than micro VCs, but this segment is one of the best to invest in. You can find seasoned VC firms with a terrific track record and a conviction-based strategy that make them successful in the market, or you can find good managers consistently performing between 2x and 3x (18%). At the same time, as shown in the performance data, there is a layer of noise from VCs that are good at raising funds but then perform below the top tier. In this category, LPs must be able to pick the right ones, as the risk of achieving less than 1x returns is quite high (35%).

Mid & Big VCs lights and shades: it’s harder to deliver top performance, as you need more than just a couple of home runs in your portfolio - only 22% have returned more than 2x MoM. That said, there’s a positive side to investing in these funds: less risk, as we’ll see later, and solid IRR since most funds in this category focus on growth and late-stage investments (which take less time to realize). Last note, LPs can find extraordinary early-stage investors here, though getting an allocation can be challenging.

Big & Multi Assets complex to return: there’s not much to say, as the performance speaks for itself. Almost half of the funds (47%) have returned less than 1x, while 48% are stuck between 1x and 2x. Returning this size and generating good performance is no easy feat. Of course, this doesn’t represent the entire world of Big & Multi-Asset firms, but it still highlights the complexity of these large funds.

Beyond performance, we felt it was also important to assess the risk of investing in the different buckets. To do this, we used the interquartile range.

Interquartile range

The interquartile range is a measure of statistical dispersion. It shows the spread of data within a dataset. In the “private fund space”, it is used to assess risk by calculating the difference between the third quartile (Q3) and the first quartile (Q1), to understand the "distance" between top-tier and low-performing funds.

The higher the return, the higher the risk. Micro and mid VCs have the widest interquartile range, followed by small funds. As with any investment, achieving high returns comes with a corresponding level of risk, but that doesn’t mean you’ll lose your money - there’s more volatility between the top and bottom quartiles (crucial in picking the right manager).

Linear Regression

After analysing the dispersion, we explored the correlation between performance and fund size.

DPI

IRR

As expected, the results showed an inverse relationship - the more you raise, the harder it is to outperform. Of course, fund size isn’t the only factor influencing performance (R² is quite low), but it can significantly impact your final results, shaping your strategy and brand building. The key point is that you shouldn’t raise more than you need, especially in today’s crowded and competitive landscape.

Paradox

According to Pitchbook, we’re seeing a steady rise in big and multi-asset funds, even though their performance has remained relatively weak. In the last 7 years, funds over $1B have more than doubled in capital raised compared to the previous 8 years, while other “sizes” have decreased.

The reasons behind the rise of bigger funds

The old saying “You’ll never be fired for buying IBM” applies to venture capital as most influential brands are agglomerating even more capital for the following reasons:

LPs (typically big institutions with low-risk profiles and tons of capital to deploy) look for safer investments in recognized brands, especially in turbulent periods with a high cost of capital and low performance;

Complexity of the market in small funds, usually emerging managers (1-3 vintage), makes stock picking tough - why bet on something unknown when you can re-up in established ones raising more and more capital?

LP type & their cost-benefit analysis. The most active LPs in this period are big endowments, with the mandate to deploy capital. They have big checks & small teams → smaller the portfolio the better. Thus, big funds represent a nice pool to “safely” deploy a big chunk of capital.

Ego - as a GP, you might think that being able to raise large funds means you’re a top-tier investor or a well-known manager in the field (it’s easier when cash is cheap, like in 2020-21). This is quite widespread in crowded markets where you want to establish your brand - tough, in most cases, this doesn’t work, weakening your track record. We’ve seen good names scale back their fund size once realized this.

Bigger funds on the rise: So What?

Despite evidence demonstrating that discipline is needed when it comes to size, the increasing number of bigger funds is a reality (as proved above).

We see two main consequences with rippling implications for the ecosystem:

“Super” Outlier Investment Only: As the number of prominent players is becoming bigger and “multistaged,” the implicit criteria for a successful venture investment is multibillion-dollar outcomes as they’re the only ones capable of returning the fund. You need to own 10% of a $10 billion company for a 1x on a $1 Bn-only fund.

Low price sensitivity: the combination of big firms and focus on extreme outcomes is distorting prices along the value chain. Paying 50 or 100 Mn can make little difference if you’re employing a <1% of the total capital raised to buy 10% of a company that you expect to return > $ 2-3 Bn. Especially at the earliest stages, it becomes a call option.

Some Implications We See

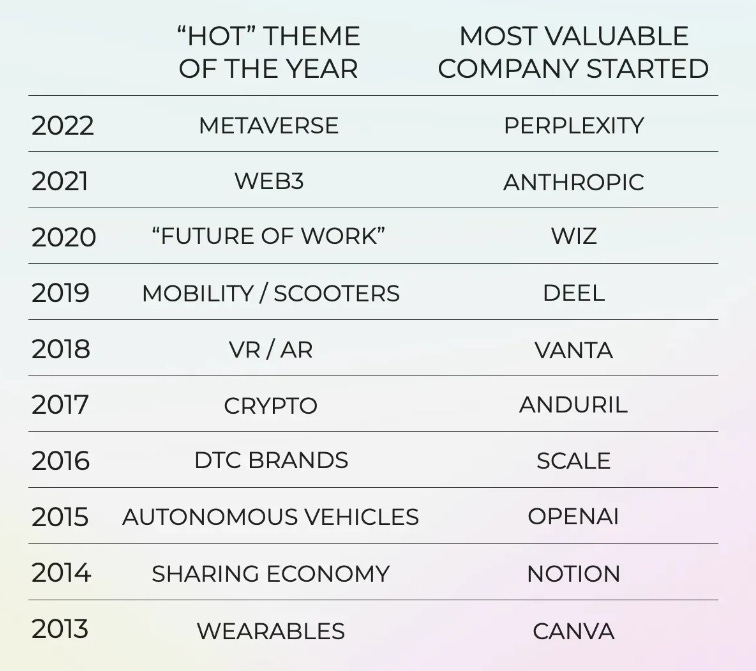

Adverse selection for unconventional ideas. Not always the most valuable company in a given vintage belonged to the year’s hottest category. See the pic below. The pressure to deliver outstanding outcomes may GPs to fund more conventional bets.

From Digital Native Substack - link here Compression of average returns for the assets class. On one hand, we have inflation of early-stage rounds due to the price insensitivity of multistage firms. On the other hand, companies are supported in their journey and, especially in their exit process only if they demonstrate they can deliver outside results. A lot of reasonable exits may not happen due to diverging interests in the captable. Lastly, it’s difficult to escape venture math. If the majority of the money is deployed of out multi-billion dollar funds and the average early-stage valuation rises while business histories showed us that an average of 7 companies per year can turn out to be +$5 Bn companies (here is a detailed breakdown) the return profiles risk to be different than the ones in the charts above.

Artisanal firms with a solid thesis and clear differentiation. White space is opening back to “small firms” with talented GPs, a lean team, an insightful thesis and a strong value prop to provide founders with a product more tailored to their needs and aligned with their interests is opening up. The majority of these firms are spinning out from multi-stage brands where politics, team management and other non-investing activities. The latter are also backers, underlining the validity of such a value prop. Especially in the earliest stage.

Manager selections and thus competition in investing in top managers increases. Good fund managers can easily attract capital. LPs will have to do their homework to win space in the capable. This competitive pressure will lead to an increasing professionalization of LP evaluation processes.

Closing Remarks

Fund size remains one of the key (first) questions fund managers should ask in drafting their plans. It underpins everything important for the firm. As always, there’s no “perfect” amount to raise - it depends on different factors and strategies. The key is not to raise more than you need, by prioritizing returns over fees.

The topic in recent years has become controversial with several firms doing what seemed impossible only 15 years ago by raising +$1 Bn funds. Although data suggests that discipline in fund size can deliver better returns, the big firms have been agglomerating most of the LPs’ capital over the last years, especially in ‘24.

The implications are broader and impact the whole ecosystem, from high prices to misalignment between money managers and founders.

Venture is a long feedback cycle business. We’ll have to wait at least 5 years to see how this will play out, but we’re sure it’ll be interesting to watch.

By Giovanni Paratore and Tommaso Moraca

Nice one!

Hello there,

Huge Respect for your work!

New here. No huge reader base Yet.

But the work has waited long to be spoken.

Its truths have roots older than this platform.

My Sub-stack Purpose

To seed, build, and nurture timeless, intangible human capitals — such as resilience, trust, truth, evolution, fulfilment, quality, peace, patience, discipline, relationships and conviction — in order to elevate human judgment, deepen relationships, and restore sacred trusteeship and stewardship of long-term firm value across generations.

A refreshing take on our business world and capitalism.

A reflection on why today’s capital architectures—PE, VC, Hedge funds, SPAC, Alt funds, Rollups—mostly fail to build and nuture what time can trust.

“Built to Be Left.”

A quiet anatomy of extraction, abandonment, and the collapse of stewardship.

"Principal-Agent Risk is not a flaw in the system.

It is the system’s operating principle”

Experience first. Return if it speaks to you.

- The Silent Treasury

https://tinyurl.com/48m97w5e